Errant is fucking cool, man.

I learned of this TTRPG thanks to Walton Wood’s interview with the creator of Errant, Ava Islam, in the latest issue of WYRD SCIENCE. It included a great breakdown on the principles that went into the game, as well as some juicy discourse on the OSR and what it means to cater to an experience for a group of players.

I remember being so moved by Ava’s words on what kind of real person would become an “adventurer” (colonial subjects in a cycle as revanchistic as the OSR itself), as well as the poetic comparison of Bengali makha to TTRPGs that I immediately put my magazine down, went on my phone and paid for a copy of the book.

And it did not disappoint!

So, what’s the big deal?

Errant describes itself as being “rules light, procedure heavy”. It began as an attempt by one person to trawl the blog-o-sphere for ways to run the ups and downs of scoundrel tomb-robbers, becoming dense with procedures to the point where a team of peoplegot behind it (now Kill Jester) and have turned it into its own standalone book. There’s one resolution mechanic: roll a d20 under the relevant stat (except when it’s not, see below). Meanwhile, using said mechanic there’s a veritable cookbook of recipes for fun, in-depth adventuring to facilitate outcasts relying on luck and grit to turn their fortunes around.

Want to facilitate a legal trial? There’s procedure for that. (you throw too many balls of fire in basements full of rats and you’re bound to build an Arson case). Want to facilitate a building collapsing in on a party, and they need to move or be crushed under the weight of their ignored consequences? There’s procedure for that.

There’s procedure for overland travel, for exploring tombs, donjons and any dangerous environment consisting of X number of rooms.

There’s a veritable charcuterie of options, sub-systems and storytelling devices for GMs new and venerable. It’s also, of course, fully modular. Errant is a vehicle for delivering a “classic OSR” experience but one spiced and flavored to your preferences; or perhaps more importantly, to your table’s preferences.

Minigame as Procedure

My favorite example is Lockpicking. The book provides a mini-game to complicate the act of picking a lock beyond the mere act of “roll a d20, it opens or it doesn’t”. It makes lockpicking into a kind of system-mastery: a roll is required but only after some combination of the three actions Twist, Tap and Turn. The 13 different kinds of locks are opened with a combination of these three. A Crude Lock for example requires Turn, Tap, Turn and has no additional modifier. An Iron Lock, in contrast, requires Tap, Turn, Tap and starts off Cracked. This cracked modifier means that the first action will always be correct, meaning any bugler is already 1/3 of the way through opening it with their tools.

So, prospective thieves need to roll, but three actions are required for every lock. The first wrong action makes it stiff, and choosing another wrong action while stiff jams the lock. This mini-game creates narrative tension of trying to pick a lock under pressure, while also allowing a player to pull off the iconic criminal move of coming up to a lock and letting out a cheeky “Oh, I’ve seen this before. No sweat.” And then actually executing it properly.

It’s intricate on its face, can provide for some serious drama, and takes up only 2 pages of the Errant book. I can see my friend Jess - an itinerant thief player, she knows what she likes - really enjoying this subsystem. It makes lock-picking overall more complicated in exchange for increasing the reward of knowing how to pick locks, bringing you closer to the drama and character.

If another friend of mine was playing a rogue, or a whole party wanted to try and pick locks…I think they’d hate it! And that’s okay!

Because this is what it means to have a game truly be modular.

Include what you and your players like, and leave the rest.

A simple mantra repeated often in online circles, but it’s so energizing to see a TTRPG putting this at the core of its philosophy and its design.

Don’t like how the game uses Speed Dice to see how far you can travel in a fight? Throw it out, and include what you like. (This also seems to be of mind to the designers, who have included quite a bit on Speed Dice in their Errata).

Downtime Actions

What I also admire about this game is its procedural implementation of downtime. Not every play group goes heavy on downtime. My personal group of friends - after years of encouraging - now go hard in the paint for accomplishing long term goals whenever they have significant time between adventures.

With the framework of a game like 5th Edition, I often flounder to properly facilitate crafting, alchemy or research. This seems a common experience.

One player in particular wants to work on creating a tinkerer’s space, upgrading a magic hoverboard and researching his own spells each down time. Don’t get me wrong, I love it when they cook and I’m the one who encourages it - but left to my own devices with a framework like 5E D&D, I often worry about letting them down and not balancing the cost of “You do X in Y units of time”, or worry that I’m being too granular and not letting them actually accomplish their goals.

Errant fixes that from the get-go. Downtime is a kind of turn with steps like anything else. It slows things down to the pace of a month, and gives concrete progress trackers to tasks and projects. Progress corresponds to time. Players can see from the beginning that time is a resource they can try and squeeze benefits out of - new spells, weapons and armor, investments in strongholds - as the forces of their antagonists continue to march along as well.

This framework is hard to port directly over to 5th Edition, but it has really been helping me try and execute a lot of the fun downtime activities my players want to engage in, allowing the players to figure out “okay I’ll need to spend 3 Downtime Turns making progress on this. Do I do this, or work on the thing that requires 1 Downtime turn?” Making interesting decisions is a core part of a fun ttrpg for me, and this lets the system and the players figure it out too.

That Resolution Mechanic

So, back to the game’s definition of “rules light”. Originally when I tried reading the rules reference, I got confused. After rereading I think I’ve figured it out to the point where I can prevent others from being confused.

Errant has 4 stats. All rolls fall under Phys, Skill, Mind or Pres. Higher stats are better because you need to roll under that number to succeed. This means on an average task, rolling a 1 might be better than a 20!

Then, we must take into account DV or Difficulty Value.

When a GM considers the difficulty of a task, they can decide that extenuating circumstances are making it more unlikely to succeed. The DV is the floor of the D20 resolution, and the GM is encouraged to raise it in increments of 2. By default DV is 0, meaning you just need to roll under your stat to succeed.

Having a DV of 2 creates a narrower band: you must roll under your stat AND a 2 or more. This confused me upon first reading, picturing having to create a sliding scale every time, but all it means it that often the GM will decide that a 1 is a failure after all. Or, if the DV is 4 or greater, the player must hit a narrow band (less than say a 13 but also 5 or greater, for example).

This is a different way of handling resolution, but this is an accounting of a kind of math that many people running or playing TTRPGs do already. They do the math of “I have +X to this, so I need at least a Y or greater on the die…” before they roll.

Errant accounts for that in its resolution mechanic from the jump, often shifting success to be the middle of a D20 instead of its upper reaches. Like any ttrpg as well, players can (and are encouraged!) to argue what the position or impact of a task is before the GM sets it. Many of the fun abilities or magics character have access to help achieve success by lowering the DV of difficult tasks, so the GM should be raising it when the odds are against the players.

Acquired Taste

I can also see why some might not like Errant. It’s got a certain vibe that many OSR games have of being hands-off; straight to the point with rules and mechanics and then moving on to the next thing. I prefer this style. I’ve been in the hobby for many years, I love reading new TTRPGs and exploring why they work, and so it’s a core assumption for me that if something is not explained, either it’s up to interpretation or you’re overthinking it and the issue is much simpler than you expect.

This comes from being used to bloated games (Cough, 5E) that feel the need to explain everything in explicit detail, and so when you don’t have that it fees lacking even though you really have all you need.

Another way to think of this is that your hands are not being held. The TTRPG believes in your ability to figure things out, and you should have the confidence to believe so too. And I love that. I want to be taken seriously as a reader, and I want structure way more than I want bloat or even flavor text.

Errant has that structure and it also has focus. It tells a very specific story of societal outcasts so down on their luck that exploring monster-filled donjons is their logical next course of action. It’s way less concerned with subverting the colonial underpinnings of adventure games; instead it’s far more interested in owning up to it, rather than putting up a facade or front. It’s picaresque - that classic roguish drama that itself came to American literature by way of Spain - and is designed to facilitate stories of indecent folk acquiring wealth and wasting it on their vain pursuits.

So, for those looking for ttrpgs to tell stories beyond heroic adventure, Errant might not be their cup of tea. And that’s okay, since the game is clear in what it wants to do! But man, do I want to run this so bad.

Every GM Has a Game Designer In Them

If the opposite of bloat is shrink, some might turn their nose at what could be perceived as content “shrink”. It’s become common in fantasy TTRPGs to open a spread of different options to browse, and Errant rejects that by having four classes that are well thought-out and evocative, and telling the player to come up with abilities and work with their GM to implement them. I think this is amazing! Certain groups of players enjoy a wealth of options, but this game supports creating bespoke set pieces to help a player live out their fantasy. For example…

The Zealot class benefits from taking items from the world and consecrating them as Relics, and there are four different kinds of Relics you can consecrate. The Zealot has formed a covenant with a divine power, and they can beseech that power for Miracles that fall within their spheres of influence. I find this appealing because the nature of the God/Goddess/Power defines the character as much as their class abilities. Calling upon too powerful of a miracle has consequences, and every God inflicts woe upon their faithful in different ways.

And while there’s only 1 Covenant in the book, there are robust tables and guidelines for a player making their own to suit the needs of their prospective Zealot.

Errant is a game that will require some design work. Players are encouraged to be creative! The whole point of a ttrpg is that it’s a collaborative medium! I firmly believe that GMs and players that unlock the imagination that they can design fun gameplay mechanics will have so much more fun.

Every GM has got a game designer in them, somewhere!

For myself, this isn’t an obstacle. I already find myself in a group where everybody has played 5E for so long that they’re already coming up with their own ancestries, class features or gestalt builds to have fun. They want to try new stuff and they also really enjoying collaborating and designing. It’s made my games more complex, for sure, but vastly more rewarding. That kind of dynamic is something I really treasure, but struggled to create my own frameworks to help them actually execute it at the table.

Thankfully, Errant has us covered.

Speaking of Covenants and options, I made one!

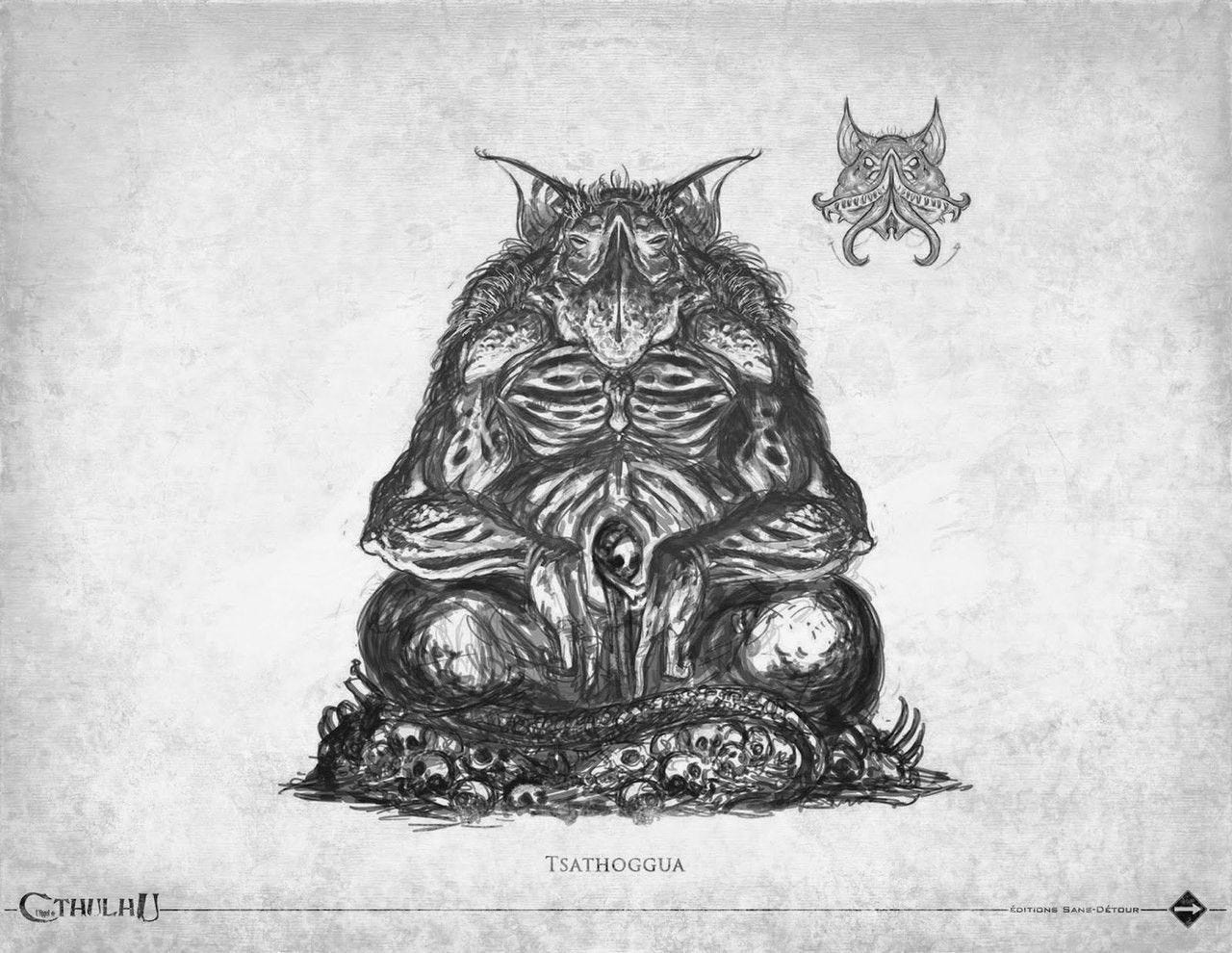

Behold, the stars are not right, and The Old Ones stir from their slumber. In divine slothfulness, TSATHOGGUA awaits the sacrifice!

Check out a covenant for a God eminent in Sleep, Dreams, Hunger & Interlopers here at this link!

Tsathoggua is an alien elder being from the short stories of Clark Ashton Smith, a poet and weird-fiction writer contemporaneous with Lovecraft. They were fans of each other’s work, and Lovecaft included casual references to Tsathoggua in a few of his classic stories like At the Mountains of Madness. I borrowed/ripped off a lot of the names and supernatural entities from his Averoigne cycle of stories for a campaign I ran from 2019-2022. He’s got the purplest prose dripping with atmosphere and dread, and so I thought I’d introduce him to the Errant ecosystem.

CAS structured his Old Ones to be more like pantheons of the ancient world rather than purely incomprehensible terrors; they’re married and related to each other in a terrible and incestuous tangle. I like that take more than the purely, dreadfully unknowable. He is an alien incarnation of sloth and hunger, and unlike many high level threats to the universe Tsathoggua is so slothful that he just waits for his disciples to bring him sacrifices under one mountain in Hyperborea.

He’s a threat, but there’s no sunken R’lyeh to rise and shatter the world.

He’s h o n g r y, and if he’s not sated he’s sending evil minions after you in your nightmares!

Give Errant your attention. I fully have the bug for it :^) Please let me know what you think of my Tsathoggua covenant, and if it inspires you to grab a copy of Errant and make your own. I could see myself making several covenants for my playgroup at home, PCs depending!

Next issue I’ll be spinning a tale from The Dripping Tap about why GMs should collude with players to set up cool moments beforehand, and finally introducing the blog’s mascot.

Until then, keep being creative!