System Matters

Why Dimension20's Ravening War is the Best Case Against D&D

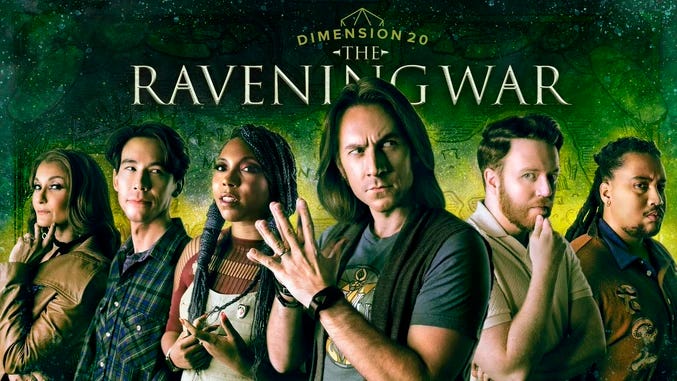

Ravening War is a Dimension20 season stacked for success: getting Critical Role’s Matthew Mercer to guest GM for a group consisting of Lou Wilson, Anjali Bhimani, Aabria Iyengar, Zac Oyama and Brennan Lee Mulligan is a stacked cast. The highly produced, well-edited show flexes the muscles of its editors, sound designers and Rick Perry’s workshop that handmakes all the sets and miniatures. After the blowout success of Starstruck (whose sets were done online through TaleSpire) and the noticable rise in quality in Neverafter, returning to one of the show’s most famous campaign settings - Game of Thrones in Candyland - proved to be one of their best.

“What’s crazier, using a real orange or not using a real orange?”

I also believe that continuing to play in Dugneons & Dragons 5E does themselves and the story they’re trying to tell a huge disservice. I think this season of Dimension20 serves as another perfect, textbook case on why the system you use to play tabletop roleplaying games does in fact matter for the kinds of stories you can tell.

Setup and Tone

Ravening War is set in the same world of Calorum that A Crown of Candy takes place in, only decades prior. To continue the Game of Thrones comparison, this season promised to be The Robert’s Rebellion to GoT’s War of Five Kings, to see the developing bloodshed and to take part in a low-fantasy high-medieval world of political intrigue, also involving heaps of food puns.

I fucking love it. And yet-

Five episodes in, with the finale premiering tonight, I have a major criticism: this really hasn’t been the political intrigue, high-medieval season that was promised.

The characters engage in scheming and plotting, for sure. Mercer utilizes time jumps to zoom in on points of tension and drama during the long, drawn out course of the war that sets up the political drama of the future. Characters assassinate rivals, they plead and engage in diplomacy or marriage alliances to secure their futures, and even become entangled in an international conspiracy.

[Spoilers for episodes 3 and 4 of Ravening War]

And then they stop.

With the cosmic, eye-opening reveal of Saprophus and the secret mushroom kingdom, the game puts aside the facilitation of political machination and schemes to do underground exploration. The seventh kingdom of Calorum was an incredibly effective reveal to me - as I believe it was to the players at the table, which is even more important - that seemed to compliment the setting without overstepping its status as a prequel series.

Yet after having signed up for another Game of Thrones in Candyland story, the gameplay turns from intrigue to adventure in the most archetypal, Gygaxian sense: they start exploring caves room by room, killing monsters and taking treasure, romping through underground societies they have no experience with looking for what will either be their great reward or a great terror to fight.

“Just Doing It”

The jarring shift from lengthy intrigue to adventure doesn’t just have to do with the myriad problems of having a highly focused, highly produced show. It’s the game system itself. The horrifying, wonderful hook of the first three episodes is all facilitated by Matthew Mercer, the rules of 5E either playing no role or actively hindering the story.

This isn’t because we have Mercer at the head of the table instead of Mulligan, either.

In other words…the best, most unique parts of Ravening War (in my mind) are facilitated back and forth between the GM and the player(s) purely through fiat. Which he’s capable of, certainly! But it’s way more work than the average GM should feel necessary, nor ever expect of themselves.

For example:

A player wants to assassinate a rival? The GM checks his notes and thinks to himself about how likely it’d be, what advantages they have, what place they’re at in the story. And then through feel sets a DC, and the player either meets it or doesn’t, either kills them or doesn’t. A binary win or lose scenario which, while the player suggests the course of action the GM is the one that makes decisions such as:

How difficult is it?

Are there complications?

How much danger should I communicate to the player, how much warning?

Great storytelling muscles, it’s not because of D&D.

Brennan Lee Mulligan once said:

“Dungeons & Dragons is fundamentally a storytelling medium with a game stapled to it” which is a statement I couldn’t disagree-with more. The kinds of stories that can be told exist within a discourse of:

What the characters abilities and powers do

What they care about

What the game rewards characters for doing (XP, milestone, etc)

Dungeons & Dragons is a game that concerns itself with fighting and killing, characters largely care about killing monsters and acquiring treasure to increase in power, and the game rewards players for said killing. XP is largely out of style and replaced with milestone XP these days, but those milestones often involve a grandiose boss battle or the completing of a quest or journey.

This is the discourse of Dungeons & Dragons. It’s not an indictment either, necessarily, but it’s the ideology or unspoken assumptions that games fall under. And those continuing to run 5E and acknowledging those realities still engage with them, for the purpose of subversion.

We live in an era where many people are familiar with game systems that actually care about degrees of success and difficulty or political intrigue: Blades in the Dark, Night’s Black Agents, World of Darkness, Worlds Without Number. Games where characters have powers and abilities tied to making plans and scheming, uncovering clues and negotiating deals, and are rewarded for doing so. Games where GMs have comprehensive frameworks or support for running factions behind the scenes.

D&D is the perfect tool for fantasy adventure and not political intrigue, which is why the delve into Saprophus feels off, but only slightly so. The GM and players clearly want to tell a story of warring lords bringing death and ruin to a magic-lite land, but they are speaking in the language of 5E: half of them have levels in Bard, the Telepathic feat and use Silvery Barbs because it’s one of the few ways to interact with threats. They leave the informal, at-the-table realm of setting goals and achieving them, instead delving into caves to kill monsters and cultists.

Similar conclusions could be drawn from their last two seasons as well: many homebrew rules were added to Neverafter to make the characters feel threatened, but they never actually engaged in gameplay mechanics that reinforced standard facets of horror like powerlessness. Starstruck used a hack of “Star Wars in 5E”, which was cool but had me shaking my monitor chanting “oh my God just play another game! There are so many sci-fi games!”

What’s crazier, using a heroic combat simulator to run a game of scheming and plotting, or not using one?

Conclusion

There are several takeaways. Ravening War and the whole Dimension20 team are incredible, this season is some of their best work and I’ve seriously enjoyed watching. I’m hyped for the finale tonight, and think it’s incredible meaningful that Mercer and Mulligan have both gotten to facilitate stories for each other in worlds of their own creation. That fucking rips.

Another takeaway, like I always say on this blog, that there are games other than 5E. Dimension20 is Dropout’s “D&D Show” but I can more clearly see it hindering the kinds of stories they’re trying to tell. The sudden diverge into adventuring to a hidden kingdom has been a point of discussion online as well, and I think it makes perfect sense when one understands that…of course they can only do so much intrigue, since it’s all vibes. They’re speaking the language of plundering and fighting, trying to tell a story of whispers, plotting and alliance-building.

Explore other ttrpgs, consider sharing them with your friends. Tune into the Ravening War finale. Play other games.

And, above all, keep being creative!

Great observation. I'm coming to think of D&D as the Monopoly of RPGs (in at least two senses). It's time the RPG world pivoted, as did the boardgame world post Catan.